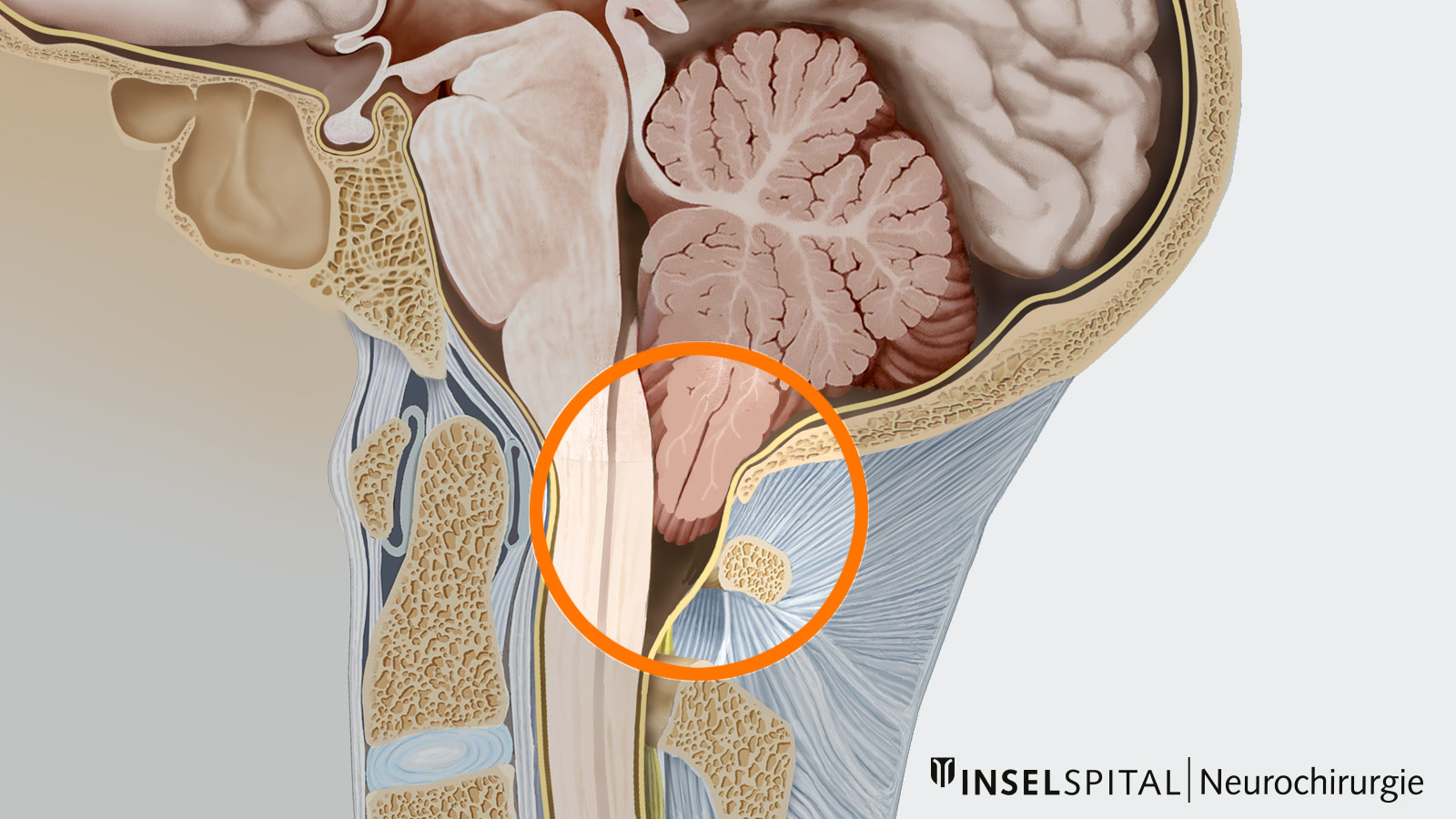

The Chiari malformation (formerly known as Arnold-Chiari malformation) comprises a series of congenital malformations in the posterior fossa where parts of the cerebellum are pushed through a natural opening at the base of the skull into the upper part of the spinal canal. This can block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and lead to problems such as headaches, neck pain, balance problems and other neurological symptoms. There are different types of Chiari malformation, of which type I is the most common. Affected patients typically become symptomatic in adolescence or young adulthood. Treatment depends on the severity of the symptoms and the malformation.

Chiari malformation type I

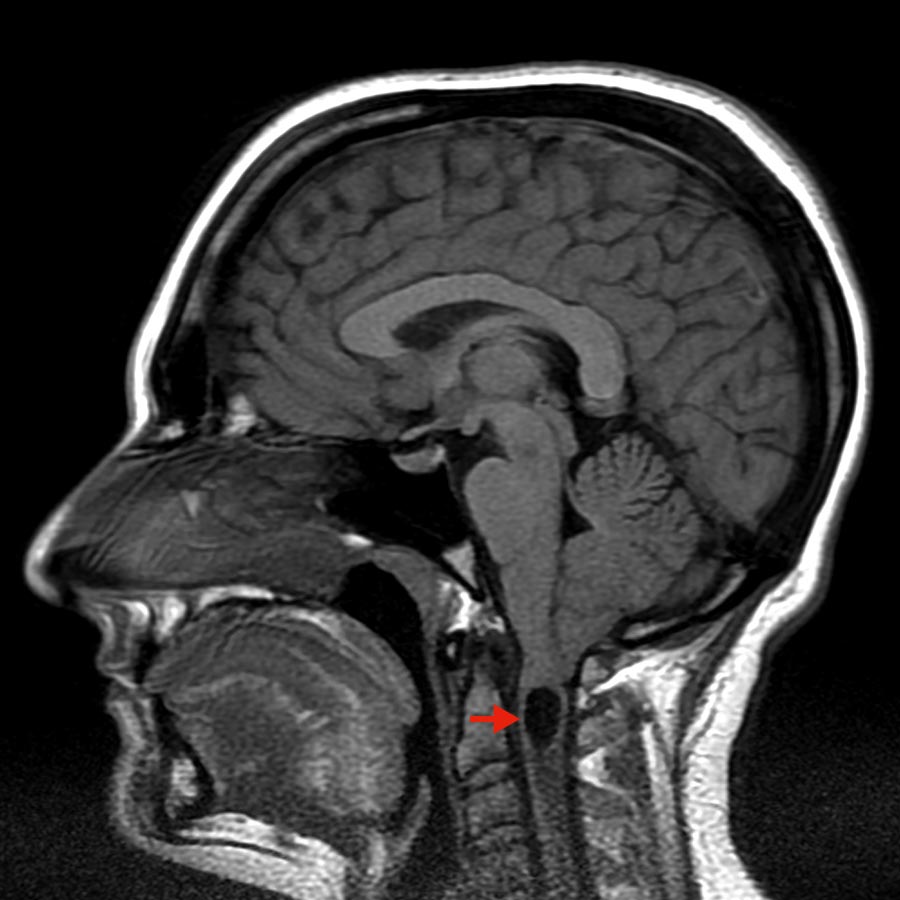

Approximately 1% of all healthy adults who undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head show a caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils, that is, a displacement of parts of the cerebellum downwards into the foramen magnum and the spinal canal *. If this displacement is more than 5 mm, it is referred to as a Chiari malformation type I. However, only 0.01 to 0.04% of those affected show symptoms. The condition can be diagnosed at any age, but often occurs in adolescence or young adulthood. Women are affected slightly more frequently than men.

Chiari malformation type II

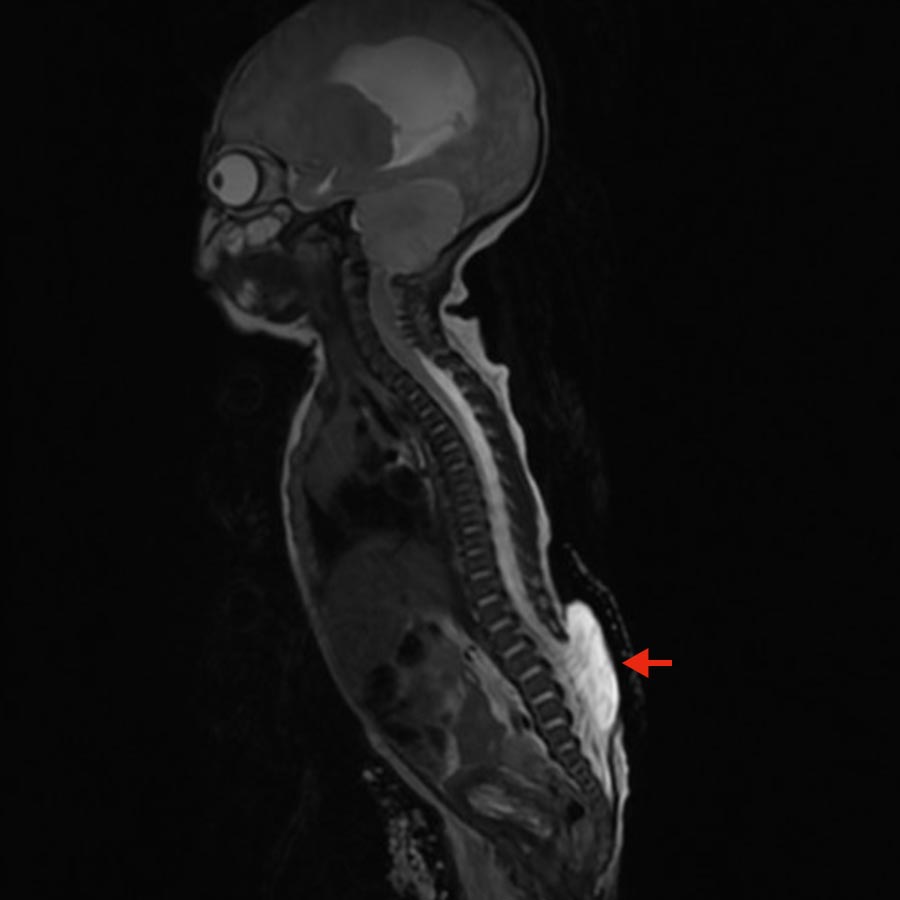

Chiari malformation type II is an anomaly that occurs in about 1 of 1000 births and is a specific form of the disease. It occurs almost exclusively in patients with spina bifida, especially in children born with an open spine (myelomeningocele ). This form of Chiari involves a displacement of both the cerebellum and parts of the brain stem into the foramen magnum and the spinal canal.

Due to improved prenatal diagnostics and preventive measures such as the intake of folic acid during pregnancy, the rate of spina bifida and thus also Chiari II malformation is declining in many countries.

Chiari malformation type I

Chiari malformation type I comprises a heterogeneous group of posterior fossa abnormalities with the common feature of impaired cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation in the craniocervical area. It is caused by caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils into the foramen magnum, the exit canal of the spinal cord from the base of the skull. This may result in compression of the brainstem, hydrocephalus (accumulation of CSF in the cerebrospinal fluid chambers), or syringomyelia (cavity formation in the spinal cord).

The most common symptoms are:

- pain in the head or neck

- possible radiation of symptoms to arms or legs

- weakness in one or more extremities

- sensory disorders in one or more extremities

- unsteadiness of gait

- sometimes also visual disturbances (double images), swallowing difficulties (dysphagia), tinnitus or speech disorders

- dizziness, coordination disorders and also breathing disorders (so-called central sleep apnea syndrome)

Chiari malformation type II

In this form of malformation, the cerebellar tonsils, as well as the cerebellum and brainstem, are displaced downward and put the lower cranial nerves under tension. Most often, this also causes n hydrocephalus. This malformation is often associated with an open spine (myelomeningocele), a serious developmental disorder at the embryonic stage in which the neural tube, from which the spinal cord originates, is not completely closed.

Typical symptoms occur in childhood and include:

- dysphagia

- breathing difficulties (dyspnea)

- breath pauses (apnea)

- high-pitched, wheezing breath sounds (stridor)

- aspiration (inhalation of fluids and saliva)

- paresis of the arms

- paresis of arms and legs (tetraparesis)

How is Chiari malformation diagnosed?

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the skull and cervical spine is the diagnostic procedure of choice. Real-time MRI (also called MR fluoroscopy) allows continuous observation in real time and displays motion as a series of images. This can be helpful in assessing CSF flow through the foramen magnum.

Chiari malformation type I

Often, Chiari malformation type I is discovered incidentally and patients are asymptomatic. In these cases, surgery is usually not necessary. However, in case of asymptomatic Chiari malformation type I associated with cervical syringomyelia it must be discussed individually with the patient whether surgery is advisable.

In symptomatic Chiari, there is a clear indication for surgery and the symptoms usually respond well to surgery. In the case of prolonged weakness, sleep apnea syndrome or gait disturbances, complete recovery does not always occur. For this reason, surgery should be performed early if symptoms are present.

The goal of surgery is the decompression of the posterior fossa to restore normal cerebrospinal fluid drainage. There are various surgical procedures that differ in terms of their invasiveness, chances of success and risk profile.

The surgery always involves a suboccipital craniectomy. This means that part of the skull bone in the area of the foramen magnum is removed, a foramen magnum decompression. Subsequently, a partial removal of the posterior arch (a so-called laminectomy) of the 1st cervical vertebral body can be added. In this surgical procedure on the spine, the vertebral arch is removed together with the spinous process. Depending on the extent of the caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils, a laminectomy of the cervical vertebrae C2 and/or C3 can also be performed in individual cases.

Possible variants of the operation are

- Depending on the patient's age and severity, a bony only decompression may be sufficient *, *, *. The free and unimpeded pulsation of the cerebrospinal fluid in the direction of the spinal canal can be checked during the operation using ultrasound to determine whether the dura should be opened.

- If this does not lead to sufficient relief or if there are preoperative signs of very high pressure, it is possible to open the dura and perform an expansion plasty in addition to decompressing the posterior fossa as a further intraoperative step. *, *

- If opening and expanding the dura is not sufficient, the cerebellar tonsils can also be shrunk or removed. *

Chiari malformation type II

Again, treatment can involve decompression of the posterior fossa via suboccipital craniectomy and laminectomy of C1. However, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt or VP shunt for short must often be implanted in advance to treat the hydrocephalus. This is a surgically created connection between the ventricular system of the brain and the abdominal cavity through which excess CSF can be drained into the abdomen, where it is reabsorbed.

Surgical risk

Various complications can occur during a surgical procedure to relieve pressure in the posterior fossa. Possible problems include inadequate pressure relief in the skull, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF leak), infections or problems with wound healing. The success and risk of the operation depend heavily on the method chosen and the severity of the condition.

There are differing views in the medical literature and in the approach taken by individual medical centers. In general, less invasive procedures carry a higher risk that the relief will not be sufficient and may require further surgery. On the other hand, a more invasive procedure increases the risk of complications during and after surgery, which may lead to further surgical interventions to treat these problems. Nevertheless, more invasive methods can reduce the risk of repeat decompression surgery.

Our experience at Inselspital

Our specialized neurosurgical team has many years of experience in the surgical treatment of Chiari malformations. Depending on the patient's individual situation, we select the most suitable surgical method. *

To ensure maximum safety for our patients during surgery, each operation is performed using the latest technological procedures. For example, we use real-time ultrasound during the operation to directly monitor the relief and individually adapt the chosen method. Continuous intraoperative monitoring can also be carried out in special cases.

For children with Chiari malformation, we work closely with our colleagues in pediatrics and neuropediatrics at the Children's Hospital.

-

Sadler B, Kuensting T, Strahle J, Park TS, Smyth M, Limbrick DD, Dobbs MB, Haller G, Gurnett CA. Prevalence and Impact of Underlying Diagnosis and Comorbidities on Chiari 1 Malformation. Pediatr Neurol. 2020 May;106:32-37. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.12.005.

-

Lin W, Duan G, Xie J, Shao J, Wang Z, Jiao B. Comparison of Results Between Posterior Fossa Decompression with and without Duraplasty for the Surgical Treatment of Chiari Malformation Type I: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018 Feb;110:460-474.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.161.

-

McClugage SG, Oakes WJ. The Chiari I malformation. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019 Sep 1;24(3):217-226. doi: 10.3171/2019.5.PEDS18382.

-

Massimi L, Frassanito P, Chieffo D, Tamburrini G, Caldarelli M. Bony Decompression for Chiari Malformation Type I: Long-Term Follow-Up. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2019;125:119-124. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62515-7_17.

-

Rehman L, Akbar H, Bokhari I, Babar AK, M Hashim AS, Arain SH. Posterior fossa decompression with duraplasty in Chiari-1 malformations. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015 Apr;25(4):254-8.

-

Beecher JS, Liu Y, Qi X, Bolognese PA. Minimally invasive subpial tonsillectomy for Chiari I decompression. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2016 Sep;158(9):1807-11. doi: 10.1007/s00701-016-2877-2.

-

Lin W, Duan G, Xie J, Shao J, Wang Z, Jiao B. Comparison of Results Between Posterior Fossa Decompression with and without Duraplasty for the Surgical Treatment of Chiari Malformation Type I: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018 Feb;110:460-474.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.161.

-

Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. Thieme; 2016:1664.

-

Chiari malformations: classification, treatment and prognosis, history and etymology.

-

Heiss J.D. Epidemiology of the Chiari I Malformation. In: Tubbs R., Oakes W. (eds) The Chiari Malformations. Springer Natur; 2013.

-

Meadows J, Kraut M, Guarnieri M, Haroun RI, Carson BS. Asymptomatic Chiari Type I malformations identified on magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:920-926.

-

Schijman E, Steinbok P. International survey on the management of Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:341-348.

-

Novegno F, Caldarelli M, Massa A et al. The natural history of the Chiari Type I anomaly. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;2:179-187.

-

Langridge B, Phillips E, Choi D. Chiari Malformation Type 1: A Systematic Review of Natural History and Conservative Management. World Neurosurg. 2017;104:213-219.

-

Lin W, Duan G, Xie J, Shao J, Wang Z, Jiao B. Comparison of Results Between Posterior Fossa Decompression with and without Duraplasty for the Surgical Treatment of Chiari Malformation Type I: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:460-474.e5.

-

Zhao JL, Li MH, Wang CL, Meng W. A Systematic Review of Chiari I Malformation: Techniques and Outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2016;88:7-14.

-

Menger R, Connor DE, Hefner M, Caldito G, Nanda A. Pseudomeningocele formation following chiari decompression: 19-year retrospective review of predisposing and prognostic factors. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:70.