When a child is diagnosed with a brain tumor, an extremely stressful time begins for the whole family. Life between home, doctor's appointments and hospital stays has to be reorganized. Families affected face a multitude of medical, psychological and organizational challenges. And always omnipresent is the great fear for the survival of the child.

What exactly does a brain tumor diagnosis mean? How do children and their families cope with the stressful treatment? What support and services are available? We asked people who can give us insight into the situation:

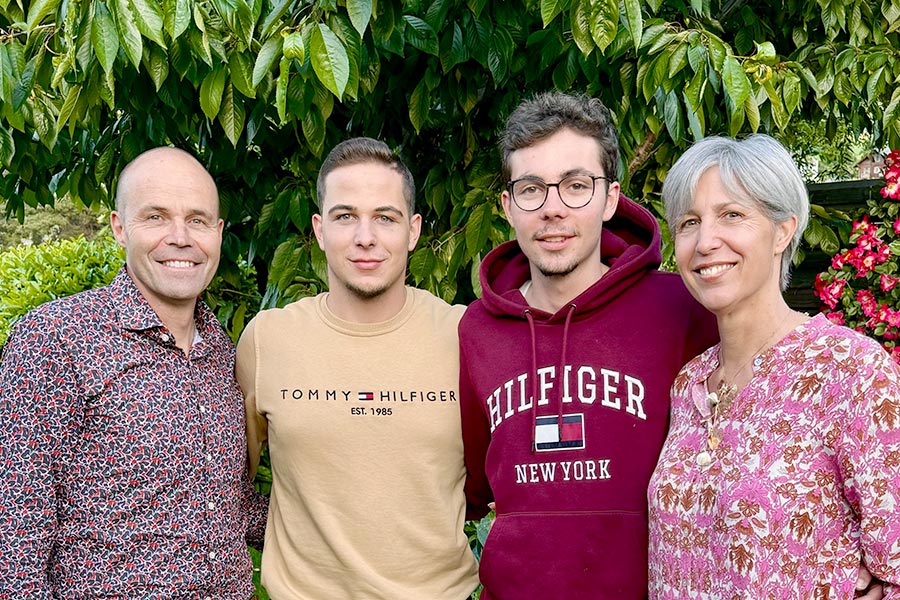

Josiane and Fabian Studer are parents of a child with a brain tumor. Their son Severin, who is now 20, was diagnosed with a brain tumor at the age of nine and treated at the Inselspital, Bern University Hospital.

We spoke to Regina Maria Gossen, MD, a pediatric oncologist and senior physician at the Children's Hospital at Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, about the medical aspects of diagnosis and treatment.

The interview

Regina Gossen, how common are brain tumors in children?

Regina Gossen: Fortunately, cancer in children is rare. In Switzerland, around 250 children develop cancer every year – around 25% of them have a brain tumor. This makes brain tumors the second most common form of cancer in children, after leukemia.

How do parents notice that their child has a brain tumor? What signs can occur?

Dr. Regina Gossen: Brain tumours can cause different symptoms depending on their location and growth rate. They often cause headaches, morning vomiting (particularly fasting vomiting), gait and vision disorders. Seizures, paralysis and personality changes can also occur. 99.9% of headaches without any other symptoms are not a sign of a brain tumor.

Where can concerned parents turn?

Dr. Regina Gossen: Parents should visit the pediatrician, especially if their child has frequent, persistent, or even worsening headaches. It makes sense to openly address concerns and fears.

If headaches are accompanied by additional symptoms, parents should consult a children's hospital quickly in consultation with their pediatrician. If a brain tumor is suspected, an MRI scan of the skull will be performed quickly to clarify the situation.

Mr. and Mrs. Studer, how did you realize that something was wrong with your child?

Josiane Studer: Severin had actually always been very healthy, active and athletic. We didn't even realize that he had a brain tumor.

How did you receive the diagnosis then?

Josiane Studer: It was a pure coincidence. Severin ran head-on into a pillar and hit his head hard. At first it didn't seem too bad. But then during the night he started vomiting and didn't stop the next day either. I got worried and took him to the emergency room at the hospital. After a few examinations, the doctors decided to do a CT scan on my son. That's when it was discovered.

How did you experience the moment of diagnosis?

Josiane Studer: For me, it was really very difficult to grasp, because my son had no symptoms at all until the time of the diagnosis. If he had already had failures, I would have understood that something was wrong, but that was not the case with Severin. He had led a completely normal life until then.

I suppressed the diagnosis immediately. To this day, I don't know whether the doctors in the emergency room really told me that Severin had a brain tumor. I can't remember it clearly. I then went home and told my husband and family that everything was fine and okay. It was only when our pediatrician called me the next day that I somehow realized it.

Regina Gossen, what types of brain tumors are most common in children?

Regina Gossen: In children, brain tumors almost always develop from the cells that naturally occur in the central nervous system. In adults, on the other hand, they are often metastases from other tumors present in the body, such as breast cancer or lung cancer.

About 25% of childhood brain tumors are benign pilocytic astrocytomas grade 1, which grow slowly and do not metastasize. Nevertheless, these tumors can cause major problems in the skull by putting pressure on brain tissue, nerves, blood vessels and cerebrospinal fluid spaces.

The second largest group of childhood brain tumors, accounting for about 20%, are the embryonal tumors. A typical example of this is medulloblastoma, a very malignant, aggressive tumor (grade 4) that occurs in the cerebellum and can cause metastases in other brain regions.

The ratio of benign to malignant brain tumors in children is about 50/50.

What is the treatment for children?

Regina Gossen: If a benign pilocytic astrocytoma is small and in a favorable location, so that it can be completely removed without injury to important brain structures, the patient is cured after surgery. If the tumor is located in an unfavorable position, the situation is much more complicated, so that the chances and risks of the various treatment options must be carefully weighed.

In the case of a malignant and aggressive tumor, a combination of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy is used in most cases for the best possible treatment. Standardized treatment protocols are also often possible for rare tumor diseases. Nevertheless, every person is different. At the beginning of brain tumor treatment, we often have to decide together with neuroradiologists and neurosurgeons what is best for the child concerned. Can the tumor be removed completely? If that is possible, wonderful. Or does it make more sense to just take a tissue sample and then decide how to proceed based on the pathology and sometimes also tumor genetics results? Sometimes it is better to do chemotherapy first to shrink the tumor and then operate. And in some cases, it is not necessary to remove the tumor radically.

Particularly in the case of malignant medulloblastoma, especially in younger children, the therapy can consist of intensive chemotherapy blocks of one week each. High-dose therapy with stem cell transplantation is also an option. In infants and toddlers, this can often avoid radiation, which is very important for long-term effects.

Overall, children generally tolerate chemotherapy much better than adults. They have fewer side effects and are often surprisingly fit. The reasons for this are probably a better metabolism, faster detoxification, and less worn-out organs. They usually compensate very, very well for chemotherapy.

Do doctors tell children when they are diagnosed?

Regina Gossen: Yes, definitely. Usually, the first conversation is only with the parents, but of course it also depends on the age of the children. Adolescents are included right away. You have to be open about it, because the children also have to endure the treatment and the complications. They need to have a chance to understand. Children also notice very clearly, even without being told, how things stand with them. And if you don't get them on board, then they are alone. So the desire to spare the children usually backfires. You also take away their opportunity to express themselves, to confide in their parents or the people treating them.

How open should parents be when communicating with their sick child and their siblings?

Regina Gossen: I recommend that parents communicate openly with their children. We as doctors, the nursing team and also the psychologists in the department can offer support in this regard. Open communication appropriate for the age – also with the siblings. This is not always one-to-one with what adults say. You have to see how it is best understood by the children.

Mr. and Mrs. Studer, how openly did you talk with your son about the diagnosis and therapy?

Josiane Studer: We communicated very openly within the family. Even with his younger brother. There was a situation before the operation. Severin said to me, «Mom, maybe the operation won't go well. If something happens to me, please don't give my heart to anyone.» He was 9 years old at the time. He obviously sensed that a difficult operation awaited him, without us telling him in detail beforehand.

What happened after the accidental brain tumor diagnosis?

Josiane Studer: Just four days after the CT, we went to the Inselspital in Bern, where an MRI was performed. For this, Severin had to be put into a closed tube. He also had to be injected with a contrast agent, which involved multiple injections. This was a real ordeal for our son.

Fabian Studer: After the MRI, we were informed that Severin's brain tumor was to be removed by surgery.

How did you deal with the fear during this time?

Josiane Studer: When the doctors first described to me all the things that could go wrong during the operation and the possible complications, I immediately said that I would not sign the consent form. He had no symptoms before the operation. I had always thought of him as a healthy child. I was just scared. The neurosurgeon treating him then told me very clearly: «Then Severin will have no future!»

Fabian Studer: I was able to react more rationally at the beginning and accepted the whole situation more quickly. My wife reacted much more emotionally. She always thought, we are signing this for our son, who was actually healthy until just now, and afterwards he may no longer be able to walk or do similar things. Ultimately, however, it was clear that we had to give our consent. There was no alternative.

How did the operation go then?

Fabian Studer: The operation took place very soon afterwards. Because the operation was going to take so long, we weren't allowed to wait on site. We then walked around Bern all day and tried to keep our minds off things. At around 5 p.m., we were informed that everything had gone well and that the tumor had been completely removed. But Severin was still asleep, so we couldn't see if he had any deficits after the operation. And we still didn't know for sure whether the tumor was benign or malignant. When Severin woke up from the anesthesia, he immediately recognized us and was able to move his legs – that was a good feeling.

What was the final diagnosis after the tissue examination?

Fabian Studer: Severin had a plexus papilloma in the right lateral ventricle, which is a benign tumor that can also become malignant.

How often did your son have to go for follow-up checks?

Fabian Studer: There was a risk that the tumor would grow again after removal. That's why Severin had to go for follow-up checks for 10 years. For the first two years, these were six-monthly checks, then annual checks. His treatment was completed after 10 years.

Regina Gossen, what support is available for children with brain tumors and their families?

Regina Gossen: Children with medulloblastoma, as well as many other brain tumors, require a comprehensive rehabilitation program that begins at the Inselspital as soon as the diagnosis is made. Neuropsychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, teachers, psychologists and social workers work closely together to support and encourage the children and their families. The mutual exchange with the medical team of pediatric oncologists, neurosurgeons and pediatric neurologists is very important for both acute and long-term care. Good medicine is teamwork!

What are the prognoses for childhood brain tumors?

Dr. Regina Gossen: It is not possible to say anything fundamental about the prognoses, simply because there is such a wide variety of different tumors that differ in terms of location, size, histological structure, operability, etc. But what applies to many children is that the tumor often becomes a chronic disease. This means that further interventions or treatments may be necessary over time. It is important to know that even in really severe cases, even with aggressive medulloblastomas and relapses, survival for years or even decades with a good quality of life can be achieved in some cases.

What are the consequences and long-term damage that children and young people have to expect?

Regina Gossen: It depends. On the one hand, there may be damage caused by the tumor itself. A visual impairment, for example, or paralysis. These symptoms usually regress to some extent, but do not always go away completely. These are the consequences of the tumor pressing on brain structures and causing damage. And then, of course, brain surgery is a major intervention that can cause injury to surrounding tissue. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy also cause damage.

The most common effects are learning difficulties, concentration problems and increased fatigue. Sometimes it only affects certain areas, and the child is then able to compensate well for this.

Particularly after radiation to the head, some of the damage only really becomes apparent in the years that follow. There are rough data indicating that children who require a full treatment including radiotherapy are on average about 10 IQ points worse than their non-ill peers.

Mr. and Mrs. Studer, is your son suffering from long-term effects?

Josiane Studer: Severin was always tested cognitively after the operation and during the annual follow-up visits. They had already noticed at school that he had some learning difficulties. Severin has trouble remembering things.

What's more, Severin developed an extreme phobia after the very first MRI scan before the operation. He can't be examined or treated without problems. You can't give him an injection, take a blood sample, or do dental work – it's all extremely problematic. Everything is only possible under anesthesia. Even today, it's still very severe.

What was the hardest part of the therapy for you?

Josiane Studer: The uncertainty. If you have never come into contact with the subject of brain tumors, you don't really understand what it means. If it's your own child who has a brain tumor, it's an unimaginable feeling. When you, as a parent, go with your child to the oncology ward and pass through the glass airlock, you enter a different world. And you feel powerless and at the mercy of others. You just hope that everything will be all right.

Did you feel that you were well looked after, informed and supported medically?

Josiane Studer: Yes, absolutely. We felt 100% very well looked after at the Inselspital. We trusted the doctors completely and were always very well informed and educated about everything.

Regina Gossen, how can children and their families best get through this period of treatment?

Regina Gossen: Open communication is an important point. It is also very important to openly look at offers of help, activities and therapy – from music therapy to occupational therapy. There is a wide range of options. You have to see what is suitable and helpful in each individual case.

Then it is also very important to look beyond the initial shock as a family and see what small islands of normality we can still have, what nice experiences we can have together that will lift our spirits, give us joy and strengthen our bond.

Another important point is not to lose contact with family and friends. This applies to both the sick child and the parents. Contact with peers is very important. If possible, there may be occasional school attendance that is not performance-oriented. Just being there is important.

At the beginning of the illness, everyone is asking questions and is concerned, and you can't do justice to that because you're usually completely occupied and overwhelmed with yourself and the situation. In the later stages of the illness, it often happens that a number of friends and family members withdraw. They don't want to ask again or don't know how to react properly because they're unsure. I believe that it is important to maintain a handful of really good relationships – the real friends you can rely on in all situations. You then have to cultivate these relationships. And you have to accept everything from these people – be it a cooked meal, babysitting, driving services – everything. Friendships sustain you.

Mr. and Mrs. Studer, how is your child today? How has he coped with and dealt with his illness?

Josiane Studer: He's doing well, he's finished his training and is now doing his vocational baccalaureate. Severin himself doesn't talk about his brain tumor at all. It was and is not an issue for him. He has somehow come to terms with that time.

When you look back at that time 11 years ago, what do you think then?

Fabian Studer: We were very lucky that Severin's tumor was discovered at an early stage and could be removed completely. And we were very lucky that the tumor was benign. Severin had no complications during the operation, did not need chemotherapy or radiation. He was able to continue his life as normal and go back to school. He didn't even have to repeat the class. We were and are very grateful for that.

Related News

- World Brain Tumor Day 2023 – We give time, we listen08.06.23 - Support services such as pastoral care and psycho-oncology are extremely valuable for brain tumor patients. We will be presenting them on World Brain…

- World Brain Tumor Day 2022 – Hand in Hand08.06.22 - High-quality, patient-oriented brain tumor therapy requires many specialists. Our team will be introducing itself on World Brain Tumor Day on June 8.

- World Brain Tumor Day 2021 – the important work of nursing experts08.06.21 - On this year's World Brain Tumor Day on June 8, we would like to highlight the immensely important work of our nursing specialists.

Related Links

- June 8 is World Brain Tumor Day!The aim of this global day of action and remembrance is to draw attention to the difficult situation of those affected and their families and to take a stand together.

- Setting an example togetherWorld Brain Tumor Day information brochure

- UCI - Bern Cancer CenterThe University Comprehensive Cancer Center Inselspital (UCI) – The Bern Cancer Center coordinates and integrates the Insel Group's services in cancer research and in the diagnosis, treatment and aftercare of cancer patients.

- Oncology at the Children's Hospital, Inselspital, Bern University HospitalThe center in Bern for children and young people with cancer

- Brain tumors in childrenWebsite of the Department of Neurosurgery with important information on tumor diseases in children, contact persons and contact details